Friday, 20 September 2019

The Crippleage Sekforde Street, Clerkenwell

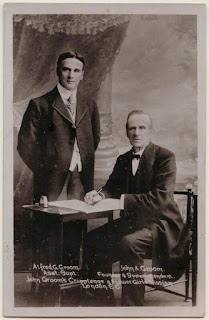

I came across an old post card from around 1907 of The Crippleage, 37 Sekforde street, Clerkenwell and done some further research.

John Alfred Groom was born in Clerkenwell in 1845. At the age of 21, he set up his own engraving business at his home on Sekforde Street, Clerkenwell.

He was a evangelical Christian and also taught at Sunday School.

John became particularly concerned with the blind and disabled girls on the streets around Farringdon Market struggling to earn a living selling flowers and watercress to passers-by. John Groom declared that his "whole nature was stirred with the deepest sympathy of pity towards the street slum children, especially the girl-child." John Groom spoke with hundreds of flower and watercress-sellers in the streets, music-halls, railways stations, and at their homes.

In 1866, he hired a large meeting room on Harp Alley near Covent Garden and founded the 'Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission', otherwise known as 'John Groom's Crippleage'. The Mission provided the girls with a free early morning mug of cocoa, and a hot dinner for which a nominal halfpenny was charged. There were also facilities for washing and for mending clothes. Groom read the girls Bible stories and also encouraged them to attend one of the three Sunday Schools he had established. Groom's activities were given a considerable boost when Lord Shaftesbury lent his support to the work, and Lady Burdett-Coutts also promoted the activities of the charity.

The Mission then subsequently moved to Laystall Street. In 1876 it transferred to larger premises at 12 Clerkenwell Close where the accommodation included a school room for 350 children and a soup kitchen fitted with coppers (utensils). In an effort to give the girls practical help, the Mission was turned into a well-organised floristry factory. The Girls' Flower Brigade, as it became known, made up bouquets which were sold from the premises. In the winter months, the girls switched to making artificial flowers, which were then becoming popular. The scheme proved successful and in 1894, the Mission moved to larger premises at Woodbridge Chapel, close to Sekforde Street.

Here are two accounts from a local paper, The Clerkenwell Lamplighter, interviewed some of the girls working there in the 1890s, they "liked making flower" but, it was noted, they were far too busy to talk.

Mrs P, as the records call her, was one of the first to use the home's services. Groom met with Mrs P living in a particularly wretched room in Plum Tree Court which she shared with her dying husband and two near-naked and malnourished children. She, like many others, sold watercress in an attempt to stay out of the workhouse, more commonly called the Bastille. On the death of her husband she entered the home.

Jenny was a young woman, with a sick brother, who worked at Groom's. She said, "I ain't a child, but I shan't be a woman 'til I'm 20, but I'm past eight I am. I can't read or write but I know how many pennies goes into a shilling." Maybe many of the home's residents were like Jenny, who were not naïve and were perhaps tentative about it, but did enter the Home. Groom's letters show his personal involvement with the care of women who used the Crippleage. Amongst his correspondence to benefactors, he discusses the minutia of running the home. Even 30 years into the life of the mission he writes to one benefactor asking for money to buy Horlicks for Miss Vince, "as her gastric troubles require its curing properties".

Donations to the charity also helped to rent houses on Sekforde Street where the girls were accommodated, and to employ 'house-mothers' to look after the girls.

Additional factories were later built nearby in Woodbridge Street and Haywards Place. The Mission's products became increasingly sophisticated and included exotic blooms for events such as exhibitions and banquets. In 1912, Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII, commissioned Groom's girls to make the flower badges for Alexandra Rose Day — raising funds for her favourite charities. After the First World War, the girls also made some of the first poppies for the Royal British Legion.

In 1890, Groom opened a home for orphaned or abandoned children at Clacton. The home also provided a holiday venue for the London flower girls.

In 1907, the official name of the charity was changed to John Groom's Crippleage and Flower Girls' Mission.

Groom's failing health led to his retirement in 1918. He spent the final year of his life at the orphanage in Clacton, where he died on December 27th, 1919. His eldest son, Alfred, continued Groom's mission work.

Due to the rising costs in 1932 of property rents in London led to the charity moving its operations to a large estate at Edgware Way, Hendon, where factory facilities and purpose built-homes were built. The factory diversified into other areas as the demand for artificial flowers started to decline. Edgware finally admitted its first male residents in 1965.

The charity changed its name in 1969 to John Groom's Association for the Disabled. The 1960s and 70s saw a decline in the organisation's involvement with the children and this aspect of its work ended in 1979.

In 1990, the charity's name changed again to become John Groom's Association for Disabled People.

In 2007, John Groom's merged with the Shaftesbury Society to form Livability, now said to be the UK's largest Christian disability charity.

Many of the houses used by Groom in and around Sekforde Street still survive, now in private residential use. The Hendon site is now covered in modern housing. The Groom's legacy is commemorated in the names of the modern roads such as Magnolia Gardens, Larkspur Grove and Roseway.

Following sources used for this post include:

The Clerkenwell post

Childrenhomes.org

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.